“Just the Facts”

Faith Seeking Understanding: Origins & Dinosaurs

August 8, 2021

Genesis 1:1-5, 20-24

John 20:30-31; 21:24-25

I was born on July 27, 1976 at 4:11 pm. at the hospital in Ransom, KS. My mom was 36 and my dad was 38. Both my dad and I are Leo’s. Those are the facts of my birth. How my mom tells it, she was so excited to have her baby—they’d been trying for years and had been close to adopting—that as soon as she went into labor, she started laughing. And even though she wasn’t supposed to, she started pushing right away, anxious to meet me.

Now, I don’t know how much of that is factual. I’ve been a woman in labor, and I do know that such an occasion can cause details to become slightly distorted—especially as they get told year after year. But whether or not those details are factual, they are absolutely true. They are true in the deepest sense. Mom had longed for a child for so long that she was ecstatic when it came time to deliver.

Truth and fact. It took me many years to begin to understand the difference. I once thought it was all the same. If it was true, then it was factual. If it wasn’t factual, then it wasn’t true.

Rachel Held Evans talks a bit about this in her book, “Inspired.” She says that we know who we are, not by the facts of the matter—when and where we were born, where we went to school, what grades we got, and so on. We know who we are by the “stories told and retold to us by our community.” If the hospital were to have gotten the time wrong on my birth certificate, it wouldn’t change who I am. It wouldn’t change whose I am.

A few years ago, I asked our Catechism students what they’re big questions of faith were, and I addressed them in a sermon series. I did that again this year. This is the first week in looking at those big faith questions. The questions haven’t changed that much. The first is always the same. What about creation, evolution, and dinosaurs? And so, we begin at the beginning.

It wasn’t until Christianity really took hold in the 4th Century that conversation about the Bible took on a question of authority. Until then, Christians didn’t have time to argue about these things. They were busy spreading the gospel and hiding from the Roman authorities. But there’s something about gaining power that distorts one’s perspective. And Christianity came into power when Constantine made it the official Roman religion. And when one has power, one fights to keep it.

This is why the discovery made by Copernicus and elaborated on by Galileo shook the religious community. Scientists could see the evidence of an Earth that was not flat but round. They could chart the elliptical orbits of the planets, the rotation of the earth, and the orbit of the moon. Everything revolved around the sun. But theologians feared the discovery. They feared it because it meant that their understanding of Scripture was wrong.

You see, the creation stories were written by people who did not yet have the benefit of a telescope. They were written by people who longed to find their place in a world that was quickly falling apart on them. Genesis 1 was first penned while the Israelites were in exile in Babylon—long after Noah and Abraham and Isaac and Jacob and Joseph and Moses. For a people who had lost access to their temple, they needed to be reminded who they were and whose they were. They needed to hear how, from the beginning, all of creation is good, formed by Adonai Elohim. They needed to know that out of chaos—the chaos at the beginning, as well as the chaos of exile—God could, indeed, make something new and beautiful. They needed to know that God had not forgotten about them.

The story of creation—all the stories of creation in Genesis and the Psalms—have absolutely nothing to do with science or history. They are poetry. They are beauty. They are—dare I say—fairy tales in the best sense of the word. Author Neil Gaiman taps into G. K. Chesterton when he says, “Fairy tales aren’t true. Fairy tales are more than true, not because they tell us that dragons exist but because they tell us that dragons can be defeated.”

The story of creation in Genesis 1 is true—not because everything was somehow made in 6 24-hr days but because it tells us that all that exists is from the song of God. And God looked upon all of it—including you—and said, “This is good. This is so very good.”

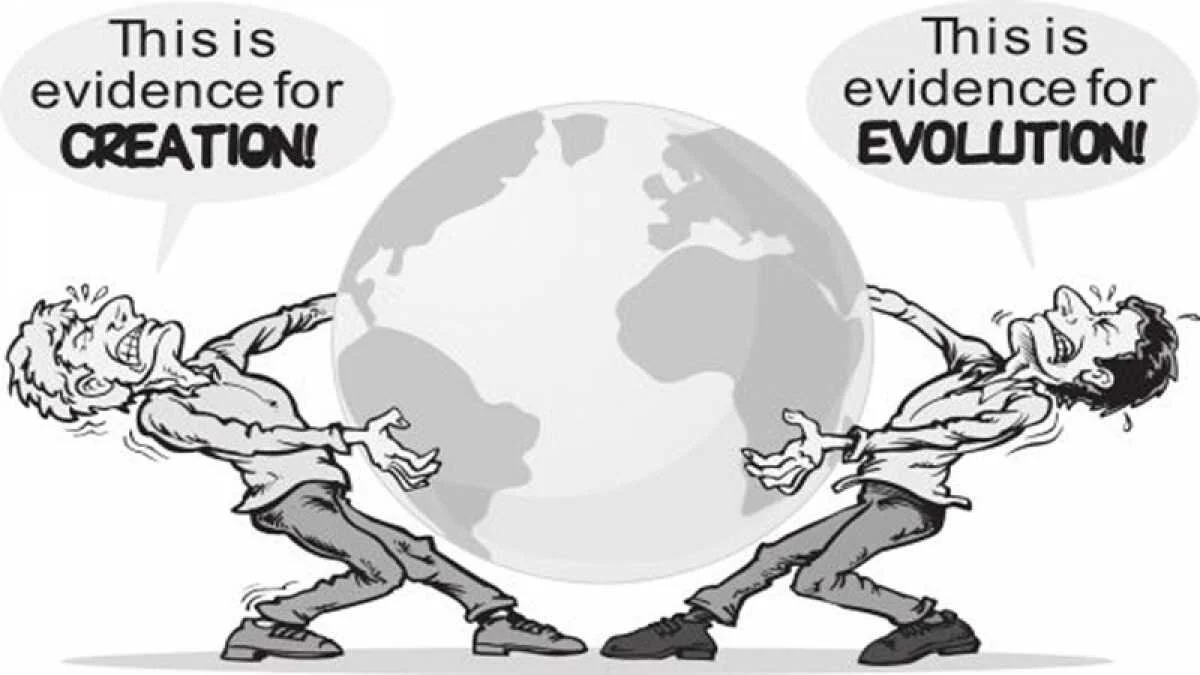

The problem that biblical literalists, as well as ardent atheists, run into is that they confuse facts and truth. If one is true, then the other cannot be. If evolution is true, the literalist believes, then Genesis 1 isn’t. And they fight tooth and nail to keep scientific discoveries at bay—even to the point of exiling or even killing people like they did in the Spanish Inquisition. And if evolution is true, the atheist believes, then the religious are foolish, naïve, even stupid for believing anything in the Bible.

But it doesn’t work that way. At least, it doesn’t have to. Sadly, it’s nearly impossible to extricate the Bible from believers who feel the need to protect it rather than seek to understand it better. And why is that? Why are we so defiant against the idea that there may be a better or different way to read Scripture?

It’s simple. The question isn’t really about religion versus science. The question at the heart of the matter is whether or not Scripture can be trusted. Because if it can’t, then as Paul says, “We of all people are to be pitied.” If Scripture can’t be trusted in the foundational stories of human history, then what does that mean when we get to the gospels? What does that mean for Jesus’ ministry? What does that mean for his death and resurrection? And besides, if this new information is true, then it means we may have understood things wrong. And no one wants to think that they’ve been wrong. Imagine the lives lost and the relationships broken because we believed so strongly that they were wrong. We’ve invested too much into being right to admit there may be new understanding.

There’s a lot at stake. And fear is at the center of it all. Madeleine L’Engle says, “It struck me that knowledge is always open to change; knowledge, not wisdom. If it is not open to change it is not knowledge, it is prejudice.” If it is not open to change, it is not knowledge; it is prejudice. Maya Angelou said, “Do the best you can until you know better; then when you know better, do better.”

This approach is not just for how we view creation and evolution. We use this as we navigate the realities of divorce; women preachers; slavery; and yes, even sexuality. As long as we read the Bible as an owner’s manual, we will forever miss the Truth within its pages. The Truth that God adores all that God has made; the Truth that our sin always comes from our desire to be gods instead of trust in the God who loves us; the Truth that God wants us to wrestle with all of this, and in doing so, we will leave with both a limp and a blessing; the Truth that the Messiah was more than a whipping boy for our bad behavior but instead showed us the length and depth of love by not retaliating but defeating death on our behalf; the Truth that heaven isn’t the reward and hell the punishment—but we’ll get to that next week.

Scripture is a living and breathing witness to a complicated relationship between God and God’s people. It was written by humans with an agenda, even while inspired by God. It is not inerrant. It contradicts itself just as my mom’s and my aunt’s recollections of a tornado have vastly different details. It is not scientifically accurate. Why should it be? Why should we expect it to be? That’s not what it’s for. It’s written to inspire, to challenge, to bring joy, to grapple with the hard questions of life. It’s written so that in reading it, we can see ourselves in its pages—just as often the antagonists as the heroes. It’s written to give us a perspective that challenges the stories of our cultures and the accepted truths of society—like ‘those who die with the most stuff wins.’

So, evolution doesn’t defy creation. The world can certainly be billions of years old—or even older. Dinosaurs obviously existed. As did so many other creatures not mentioned in holy pages and long gone from our own eyes. And these facts do not shake my faith in the Truth that God’s fingerprints are still all over the stars and the fossils and the movements of continents—and all over me and you and our lives together.

Pastor Tobi White

Our Saviour’s Lutheran Church

Lincoln, NE